Vol. 43, #2, Summer 2025

The Future of Colored Stone Grading or Hype?, GIA Drops Color/Clarity Grades for Synthetic Diamonds, In The News

- Home

- Newsletter

- Vol. 43, #2, Summer 2025

The Future of Colored Stone Grading or Hype?, GIA Drops Color/Clarity Grades for Synthetic Diamonds, In The News

|

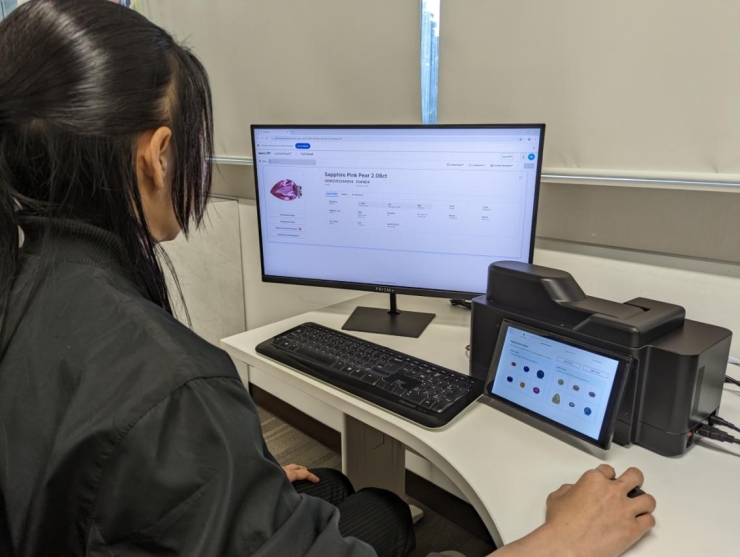

| Kromo Device: Courtesy Porolis Technologies |

Good morning, gem enthusiasts! It's time to dive into the latest shiny promise in the gem world: Porolis, a Singapore-based company touting a high-tech solution to revolutionize colored gemstone grading. With sexy buzzwords like AI, blockchain, photomicrography, and even NFTs, Porolis is positioning itself as the answer to the industry's long-standing quest for a “Magic Box” — a device that can definitively determine natural vs. synthetic, country of origin, treatments, color, clarity, and cut quality.

But does their Kroma device and Gem Vault system deliver, or is this another case of tech hype outpacing reality? Let's unpack it.

Kroma: A Game-Changer or Overpromise?

Porolis' flagship product, the Kroma device, is a compact (32x18x20 cm) all-in-one tool combining a camera, microscope, colorimeter, and computer. It scans gemstones under various lighting and optical conditions, capturing high-resolution images and 3D videos of color, structure, and inclusions. These scans are uploaded to a cloud-based AI system, GemLUX, which analyzes the data to assess color, detect treatments, and identify origins. The company claims Kroma's AI can grade gemstones objectively, using pixel-by-pixel spectral analysis and gemologist-labeled datasets. They even plan to integrate Raman laser spectroscopy for enhanced treatment detection. Sounds like a dream, right?

But here's the rub: inclusions are the key to determining a gem's origin, and that requires a robust, diverse dataset. Porolis' AI likely draws from their parent company's Gemmological Institute of Colombo (GIC), which primarily deals with Sri Lankan sapphires and rubies. What about Burmese rubies, Kashmir sapphires, Colombian emeralds, or Brazilian Paraíbas? Without a comprehensive global dataset, the AI's ability to pinpoint origins or detect treatments across all major gem species is questionable. As industry expert Cap Beesley once said, “The first 10,000 stones you grade are the toughest.” If Porolis' dataset is skewed toward Sri Lankan stones, it's hard to see Kroma being the universal “Magic Box” the industry craves.

|

| The Kromo device connected to AI database Courtesy Porolis Technologies |

Gem Vault and Blockchain: Transparency or Gimmick?

Porolis' Gem Vault system creates a digital “fingerprint” for each gemstone, based on its unique inclusions, which is stored on a blockchain for traceability. This GemCIPHER fingerprint, paired with their myGemVAULT cloud repository, aims to track a stone's journey from mine to market, ensuring authenticity and provenance. The pitch is compelling: small-scale miners, who produce 80% of colored gemstones but often lack access to certification, could benefit from affordable grading and traceability, potentially fetching fairer prices. Blockchain could also help governments curb smuggling and collect taxes by documenting stones at the source.

Yet, the blockchain isn't a cure-all. While it's immutable and transparent, its effectiveness depends on consistent adoption across the supply chain. Every miner, cutter, and trader must scan and log each stone — a logistical nightmare in the fragmented gem trade, where 80% of stones come from artisanal mines across 80 countries. Plus, blockchain doesn't verify the accuracy of the data entered; it only records it. If a stone's initial scan or AI analysis is flawed, the blockchain simply immortalizes the error. And while Porolis' Gem3D visuals are great for marketing, their practical value for serious collectors or dealers remains unproven.

The Cost Conundrum

Grading colored gemstones is pricey. Top labs like AGL, GIA, Gubelin or SSEF charge $210–$880 for a four carat full gemstone report, plus shipping and insurance, and turnaround times can stretch to two months. Porolis promises a faster, cheaper alternative, but their website and available materials are coy about pricing for Kroma or Gem Vault services. This lack of transparency raises red flags. If Porolis aims to disrupt the market, they'll need to undercut established labs significantly while proving their results are just as reliable — a tall order.

Their shared-access model, with “experience outlets” launching in Sri Lanka in June 2025, is a smart move. It lets users access scanning and certification without buying the device, potentially building a real-time dataset to refine their AI. But scaling this globally to cover all major gem types is a massive challenge, and Sri Lanka's gem-heavy environment might not translate to markets like the U.S. or Europe.

Who's Behind Porolis?

Porolis isn't a scrappy startup but a venture under the 150-year-old BP de Silva Group, a Sri Lankan conglomerate with interests in gemstones, jewelry, and tea. Their GIC lab issues reports often seen in Sri Lanka but rarely in high-end auction markets or among serious collectors. GIC's use of terms like “pigeon's blood” or “royal blue” feels more like dealer marketing than rigorous grading, casting doubt on their ability to produce a world-class AI dataset. Compare this to AGL's Prestige Grading Report, which sets the standard for detailed, objective analysis — a level Porolis is unlikely to match soon.

The AI Challenge: Garbage In, Garbage Out

AI is only as good as its data. Porolis' reliance on GIC's dataset limits its scope, and there's little evidence they've accessed the comprehensive collections held by industry leaders like Cap Beesley or labs like AGL, Gubelin or SSEF. Why would these labs share proprietary data with a competitor aiming to disrupt their business? Beesley, who likely has the best origin dataset in the world, has his own ColorScan system for color and tone grading. Sharing it with Porolis seems unlikely. Without diverse, high-quality data, Porolis' AI risks being a regional tool rather than a global standard.

Legal Risks for American Collectors

Singapore's legal system is robust, rooted in English common law, but pursuing recourse against a Singapore-based company like Porolis could be a headache for American collectors. Imagine buying an “unheated Burmese ruby” based on Porolis' AI, only for another lab to later deem it a heated Thai stone. The cost and complexity of seeking redress across borders could deter U.S. buyers, who prefer the reliability of domestic labs like AGL. Offshore certification often means sacrificing legal leverage, a risk savvy collectors won't ignore.

The Verdict: Skepticism for Now

Porolis' vision is bold, and their tech — combining AI, blockchain, and photomicrography — is intriguing. But the gem industry's complexity demands more than flashy tech. As Beesley noted, accurate origin determination is rare, even among top labs. Porolis' AI, likely trained on a limited dataset, isn't ready to rival established labs. Their blockchain and Gem Vault could enhance traceability, but only if the entire supply chain buys in — a big “if.”

We'd love to see Porolis at the 2026 Tucson Gem Show, where dealers could test Kroma with their own stones. Until then, stick with trusted labs like AGL for critical purchases. Porolis might be a step toward the “Magic Box,” but it's not there yet. Stay skeptical, and keep your loupe handy.

In a move that's raised eyebrows, the Gemological Institute of America (GIA) has scrapped its 4Cs grading system for lab-grown diamonds, replacing it with a simpler “premium” or “standard” designation. Stones that don't make the cut get no grade at all. This is GIA's third overhaul of its lab-grown grading policy in recent years, and it's a head-scratcher. According to GIA president Susan Jacques, fewer than 5% of lab-grown diamonds even pass through their labs. So why bother shaking things up for a service barely anyone uses?

A Brief History of GIA's Lab-Grown Flip-Flops

Back in mid-2020, when lab-grown diamonds were booming, GIA bowed to industry pressure and began offering full 4Cs grading, matching natural diamonds. It was a win for lab-grown producers, who could tout “GIA-graded" stones. At the time, top-tier lab-growns commanded $20,000 or more per carat, and buyers wanted the legitimacy of a GIA report. But oversupply crashed prices. Today, lab-grown diamonds sell for $50-$150 per carat, averaging around $100 - enough for a nice night out, but a far cry from their former glory . Some sellers complain lab grown diamonds are hardly worth paying for GIA's grading reports now.

GIA’s reasoning? They claim 95% of lab-grown diamonds fall into a tight color and clarity range (typically D-F, VVS-VS), making the 4Cs overkill. Their new “premium” (top-tier color/clarity) and “standard” (slightly lower but still solid) labels aim to streamline things. But this feels like GIA stepping back as the lab-grown market loses steam.

The Millennial Buyer's Plight

Picture a Millennial who bought a 3-carat lab-grown diamond engagement ring in 2020 for $60,000, banking on its GIA-graded prestige. Today, that stone’s worth about $300 at the average $100 per carat — barely enough for a fancy dinner out. Natural diamonds, despite a ~25% price drop since 2022 (per market data), still hold significant value. Lab-growns? They’ve tanked over 99% in value. The “lab-created diamond” marketing pitch misled buyers into expecting lasting worth. Spoiler: it didn’t deliver.

Why Now, GIA?

GIA's pivot smells like market opportunism. When lab-growns were hot, they hopped on the bandwagon to stay relevant. Now, with the market oversaturated and prices in freefall, they're distancing themselves. The new grading system might cut costs for growers seeking cheaper reports, but it also signals GIA's retreat from treating lab-growns as equals to natural diamonds. This move could further erode consumer confidence in lab-growns, especially for buyers already stung by their near-worthless stones.

The Bigger Picture

The lab-grown diamond industry, valued at $12 billion in 2023 but projected to slow (CAGR ~7% through 2030), is grappling with oversupply and waning demand. Retailers like Pandora and De Beers are slashing prices or shifting focus to natural diamonds, while consumer sentiment sours — 60% of buyers in recent surveys prefer natural stones for their rarity and resale value. GIA's simplified grading might streamline things for low-cost producers, but it risks alienating high-end buyers who still want detailed reports.

The Bottom Line

GIA's latest policy shift feels like a pragmatic but belated response to a market that's lost its shine. For collectors and investors, natural diamonds (especially colored diamonds) remain the safer bet — they hold value and carry a legacy. Lab-growns, despite their affordability, are proving to be a fleeting trend with little staying power. If you're buying, stick with natural stones and a trusted GIA report. Anything less, and you're rolling the dice.

While middle-market retailers brace for a slowdown, luxury's upper echelon continues to soar - underscoring a growing economic divide that may prove as precarious as it is profitable.

The ultra-rare gem market — think Kashmir sapphires, Burmese rubies, and Colombian emeralds — never seems to lose its luster. Why? It's simple: the world's wealthiest collectors, the top 10% of the global economic elite, keep demand red-hot. With stock markets soaring (the S&P 500 is up ~15% in 2025 alone) and wealth concentration growing (the top 1% now hold over 50% of global wealth), these buyers have deep pockets for one-of-a-kind stones. Whether it's a $500,000 vivid Burma blood ruby to stash in a vault, a Burma blue sapphire to flaunt at a gala, or a family heirloom to pass down, high-end gems are both status symbols and tangible assets. As long as the rich keep getting richer, the market for these rare baubles will shine on. ED

The above chart shows the price return for the Stoxx Europe Luxury 10, the S&P 500 and the FTSE All-World Consumer Discretionary indices since 2016.

Signs of strain are increasingly visible among mass-market players. Retail giants like Target and Macy's are reporting that their customers are pulling back, trading down to less expensive alternatives as tariffs and inflation weigh on household budgets. But across the gilded corridors of high-end commerce, the story is markedly different.

Italian automaker Ferrari is sticking to its 2025 guidance even as peers trim forecasts. Hermes, the Parisian icon of leather and silk, has responded to U.S. import duties not with cost-cutting but by raising prices on its signature scarves. Brunello Cucinelli, the Perugian prince of cashmere, expects double-digit sales growth through next year. And Life Time, the luxury fitness chain with $200 monthly memberships, has seen its shares rise 85% since its 2021 IPO - well ahead of discount rival Planet Fitness, according to Reuters.

The persistence of the ultra-wealthy's spending power is providing a rare pillar of strength in an otherwise uncertain macroeconomic environment. An index tracking Europe's largest luxury companies has outpaced the S&P 500 by roughly 80 percentage points over the past decade. Luxury travel is seeing a similar divergence: upscale hotels have reported 6% higher revenue per room this year, while mid-tier lodging has struggled.

The logic behind the divergence is simple: scarcity and craftsmanship. Ferrari limits production. Hermes clients wait years for a Birkin bag. Cucinelli's hand-stitched coats command prices north of $8,000. These brands are built not just on goods, but on exclusivity, and their customers are less sensitive to price shocks or economic headlines.

That insulation is quantifiable. According to Moody's Analytics, spending by the top 10% of U.S. earners rose 58% from 2020 to 2024, compared to meager real gains for everyone else once inflation is accounted for. The Federal Reserve reports that the top decile of Americans gained over $30 trillion in net worth since 2019—a 40% jump. Globally, UBS estimates the richest 1.5% hold $214 trillion, while the bottom 40% share just $2.4 trillion.

This consumption chasm is lifting profits for the luxury sector even as it exposes the fragility of

broader economic growth. For now, high-end brands may act as ballast against a slowdown.

But they are also a mirror: reflecting a bifurcated economy in which prosperity is increasingly concentrated, and resilience ever more reliant on a narrow tier of consumers.

The risk, economists warn, is that such reliance is ultimately unsustainable. If the ultra-rich pull back—or if political pressures begin to target wealth disparities more aggressively—the entire structure could wobble.

In the meantime, the champagne keeps flowing—even as the beer taps slow to a trickle.

This is an interesting update on the Big Three gemstones by a mainstream US jewelry publication. Edited for space. ED

With a long history of association with royals, the terms Burmese ruby, Colombian emerald, and Kashmir sapphire are familiar references to the most valuable gemstones to exist, and many gem dealers still argue it’s simply just the truth.

The landscape around trading the Big Three is evolving, however, as mining technology advances, sources dry up (and new ones are discovered), tastes change, and the industry navigates complex global politics. The U.S. market, driven in part by higher prices post-COVID and the lack of super-fine material available, has seen dealers recently adjust what they define, and can market, as valuable. However, the finest untreated sapphires, rubies, and emeralds still command the highest prices of any gemstone, and the appetite for the best and the rarest remains strong.

A Matter of Price

A simple understanding of the law of supply and demand can explain why prices of the Big Three, in the finest quality, are skyrocketing, but there is some nuance. Gemstone dealer and bespoke jeweler Simon Dussart of Asia Lounges explains, “There used to be three prongs in the market—the low, the mid-range, and the high range. One could argue there was a fourth one, the super high end, but that’s like, an oddity of the high end.

“But the mid-range is dying.”

The loss of interest in this category, which he describes as eye-clean material, the bread-and-butter for the average self-purchaser, is affecting the mining business, Dussart says.

“A lot of the mines are no longer profitable. They needed to have all three segments in order to produce, and now they are stuck producing for the low end, which demands increasingly lower prices, but they can’t really do it [that way], so you’ve got more and more treated materials.

“The trade has an increased demand for higher-quality material that is untreated, which is one of the reasons—but not the only reason—why the price of the material is skyrocketing.”

Since the pandemic, untreated fine sapphires have tripled in price, and Dussart says ruby was inaccessible for him even before the pandemic.

“I seldom go anywhere above 3 carats in the red and blue department,” he says. “Rubies, pre-COVID, that was out of my range anyway because it was already in the six figures, but now it’s like, forget about it. It’s impossible.”

Red-Hot Ruby

Today, untreated fine-quality ruby is exceedingly rare, making it basically a specialized market. To many in the trade, material from Myanmar’s (formerly Burma) Mogok Valley remains incomparable in quality, but production has decreased significantly.

Earlier this year, Gemfields published “Understanding the Global Supply of Emerald, Ruby and Sapphire.” The report stated that, as of 2009, more than 90 percent of the rubies with a price above $50,000 per carat auctioned at Christie’s were from Mogok, a testament to the material’s popularity and value. According to Gemfields’ report, the drop in production can be explained by the depletion of the deposits—the Mogok Valley mines as well as the deposit discovered in 1992 in nearby Mong Hsu—but also the increase in privately owned mines, which aren’t obligated to report production. The main source of ruby production today comes from deposits in northeast Mozambique, which were discovered in the late 2000s.

Although Gemfields announced a record per-carat price ($321.94) from its December 2024 auction of mixed-quality rough rubies from its Montepuez mine, those who have been attending rough sales in the region report that, generally, the quality and quantity of the material are decreasing. However, the mine remains the sole option for bigger brands that require coherence in material, such as precisely calibrated melee-size ruby with consistent color.

Rubies are also mined, on a much smaller scale, in pockets across several other countries, such as Vietnam, Tanzania, and Sri Lanka, as well as Afghanistan, though trading involving the latter poses some challenges for U.S. dealers. Last year in Afghanistan, the Taliban, which took control of the country in 2021, indicated it was going to focus on minerals to help Afghanistan’s economy. In 2022, the U.S. government issued a license allowing for economic activity in Afghanistan, as long as it was not linked to the Taliban or any persons or entities on the Office of Foreign Assets Control’s sanctions list. So, if a dealer or a company is not connected to the Taliban and not sanctioned, they could trade legally, though it is not likely, according to the Jewelers Vigilance Committee, because it would be very difficult to prove a business is unlinked to the Taliban, as the entity is the government of Afghanistan.

However, during a presentation on the colored gemstone market in Tucson, GemGuide Editor-in-Chief Brecken Branstrator said one of her sources confirmed that rough gemstones are still flowing out of Afghanistan, largely through Pakistan. International and at-source politics are an unavoidable aspect of dealing in gemstones, from years-long U.S.-imposed sanctions banning Burmese rubies to current-day criticisms of the mining concession in Mozambique as Gemfields navigates heightened illegal activity amid the country’s civil unrest.

The Other Corundum

When it comes to sapphires, many consumers are likely to first visualize a classic Kashmir blue. History, along with mainstream media and pop culture, influence what consumers, many of whom are far removed from the complex business of gemstone trading, believe gems should look like. When asked about blue sapphire, “[Consumers] most likely tell you that it’s supposed to look like Princess Diana’s sapphire,” says Dussart, who added that the vast majority of the dealers in the trade agree that the beloved British royal’s stone is “too dark.”

Sapphire represents a smaller market value than ruby and emerald, according to Gemfields’ report, and it’s an outlier in the Big Three because it’s available in a rainbow of colors.

The average consumer who assumes sapphires are out of reach for their budget may be surprised at the range of options available to them. “A lot of sapphires are not that expensive. It depends what color you want,” Dussart says. “A lot of people are exclusively looking at sapphire for the royal blue color … If you’re looking at that, then yes, prices are princess-only department.”

Fine quality, untreated sapphire is still in limited supply, and therefore, pricey. Gemfields’ report stated that its sources indicate that more than 90 percent of sapphires are treated. New discoveries have been offset by the depletion of existing mines, leading to inconsistency in overall sapphire supply over the last few decades. Production of the gemstone is relatively stable, though the overall quantity of sapphires available has decreased significantly since the 1980s.

Quality is dwindling as well, according to Dussart, and less material is filtering down into the market. With ultra-high prices for classic blue sapphires posted throughout the Tucson shows in 2024, buyers shifted focus to other shades of blue, opting for teal sapphires from Australia and the earthy, denim-blue material from Montana. However, several vendors at the 2025 trade shows in Tucson and at the Bangkok Gems & Jewelry Fair in February reported that buyers appear to be leaning back into the Ceylon blue tones. Not surprisingly, many are still hunting for top-quality material. For these untreated stones, dedicated collectors and investors appear willing to face the sticker shock.

Dealers who have the material are keenly aware that even if they are able to sell, replacing the stone will be a challenge.

Understanding Emeralds

The emerald market has experienced a similar pricing phenomenon in that vendors report buyers looking for untreated fine-quality stones come shopping with apparently no ceiling.

A variety of beryl, emerald has enjoyed a boost from the popularity of green gemstones over the last few years. It also has become a popular choice for those seeking a colorful engagement ring despite its relative softness (7.5-8) on the Mohs scale when compared with diamonds, rubies, and sapphires.

The emerald mines in Bogotá, Colombia, regarded by many as producing the world’s finest emeralds, have a history dating back more than 800 years, and they’re still producing. Neighboring Brazil also offers a consistent supply, though it produces less fine quality.

Together with Zambia, these three countries dominate the global emerald supply. In the last 40 years, there have been no major discoveries that have dramatically changed the emerald supply dynamic.

The key factors affecting volume and supply in the last four decades have been changes in mining activities, including a shift towards larger, more mechanized and formalized operations. However, the finer-quality material is becoming rarer as the appetite for untreated gems grows. “There [are] not enough stones on the market to support the demand for no-oil gemstones [regardless of origin],” says Zoe Michelou, director at Imperial Colors Ltd.

“The price has come down a little bit [for commercial-quality goods] because of economic conditions and shifting consumer demand, but it’s widely available,” Michelou says. “I don’t buy much of this quality; I go more toward the high-end quality and here, the price has gone up.” She says that, at the moment, she can’t even guarantee a customer a price for two months because it keeps climbing.

Michelou’s father, the late Jean Claude Michelou, was an emerald specialist with more than four decades of experience mining the verdant gem, so she’s familiar with the public perception of the gemstone. “In terms of demand and value in people’s minds, because of the history, Colombia will always be No. 1,” she says, adding that Colombian emeralds command premium prices in the market.

She also enjoys the look of the lighter-colored emerald material from Russia, she noted, and had some specimens at her booth at the Bangkok Gems & Jewelry Fair. She said Americans attending the show were intrigued by the material, noting, “I find they are more curious [than attendees from Europe].”

More widely available are the emeralds from Zambia, some of which Michelou says are “even more beautiful than Colombian material.” The oversupply of commercial-quality goods is impacting this African nation. The miner’s most recent emerald and ruby auctions held prior to the announcement had yielded lower-than-expected revenues, which it attributed to an oversupply of Zambian emeralds on the market at “discounted prices.” To address these challenges, the miner announced a package of measures designed to cut costs and streamline its business, which included the months-long suspension of mining at Kagem. However, some say the use of terms like “discounted prices” can give a skewed perception of the emerald market.

Grizzly Mining (the competitor Gemfields is believed to be referring to when it mentions “discounted prices”), which also mines emerald in Zambia, offered a total of 1.93 million carats in its December emerald auction. Dussart noted that while the volume of material in the Grizzly auction was high, in reality, the proportion of gem-quality material was not. Prices for the high-end material have not gone down at all. “If you look at the collections from the high jewelers, there are significantly more emeralds, and so it’s like, emeralds must be all the rage,” he says. “But no, there’s just more emerald right now on the market.”

“Gems, by definition, are freaks of nature. Once you understand that part, you understand that whatever comes out in gem form and gem quality is rare.”